zhi wei hiu

Zhi Wei Hiu breaks down and reconfigures what we think of as a photograph and the photographic. In this conversation, we talk about her pantheon of literary influences, the limits of photography, and the relationship between photography and sculpture. Born in Singapore, she now resides in Brooklyn, New York.

I hope you enjoy our conversation. It has been edited from a spoken interview and condensed for clarity.

Artwork photos and portrait courtesy of the artist

You had this great idea of starting this conversation with books, referencing some of the texts and writers that mean something to you, since that is a shared interest that has animated so much of our conversation.

Books are so important to me. My book collection is the first thing I see and the last thing I see every day. I will often let my attention be diverted by books. I find it essential to constellate my thoughts in space by making piles of books. This approach translates into how I arrange and combine materials in my studio and within the form of each work. As I’m thinking of ideas or solutions for a work, I like to feel my eyes travel across my books, feeling out the urgencies of the moment. This feels akin to leafing through a stack of photographs.

We will get to photography in a moment. As we’ve spoken, you have offered this tapestry of people, histories, and text—from Hilton Als on Robert Gober to Moyra Davey to Tim Morton’s Dark Ecology—that allows different entry points into your practice, depending on one’s familiarity or recognition of those references.

Artists function brilliantly as pollinators of information. We ingest and metabolize so much specialized information in the isolation of the studio. Sharing information is how I create porosity in the walls of my studio. What’s important to me is the social dimension to having a practice. When conversing with trusted interlocutors, the crossover in our references allows us to speak in a kind of shorthand. In a context like this, instead of talking strictly about my work, I would prefer to leave a public record of the other people who I’m reading.

How are you engaging with the books? Are you taking notes and flagging things? Is it more cursory—quick and visual?

All of the above, but I most enjoy a meandering, flaneuring, associative engagement. It’s wonderful to allow myself to be led along new avenues and trajectories.

I think of this interview between Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany in which they discuss the practice of reading several books on varying topics simultaneously, allowing disparate ideas to ricochet off each other.

Can you explain how that shows up in your work?

You can pull something from its original context and recontextualize that in your practice. It ties into appropriating images. In any given work, I’m conjugating elements, including objects that I have placed on or in my body, photographic prints, the chemical processes of analog photography, and components fabricated or cast using jewelry fabrication techniques.

Alice Notley speaks of poetry as the process of making words vibrate by placing them side by side. I spent the first twenty years of my life in Singapore, speaking what we call Singlish, a creole that blends English, Mandarin, Malay, and several dialects into a recombinant form marked by a remarkable linguistic economy. This approach to the spoken word informs my way of working between material languages.

There’s something provocative about separating a text or source from its context.

Decontextualization—such a wonderful way to create a gravitational pull.

I love traversing Clarice Lispector’s language. A triptych I made in 2024 references three versions of her short story The Egg and the Chicken: the original, written in Portuguese, and two English translations. Each work in the triptych incorporates three applications of silver: a gelatin silver print, a silverpoint drawing, and hardware cast in sterling silver. I inscribed the first page of The Egg and the Chicken on the glass protecting the print, with every instance of the word “egg” reduced to a symbol.

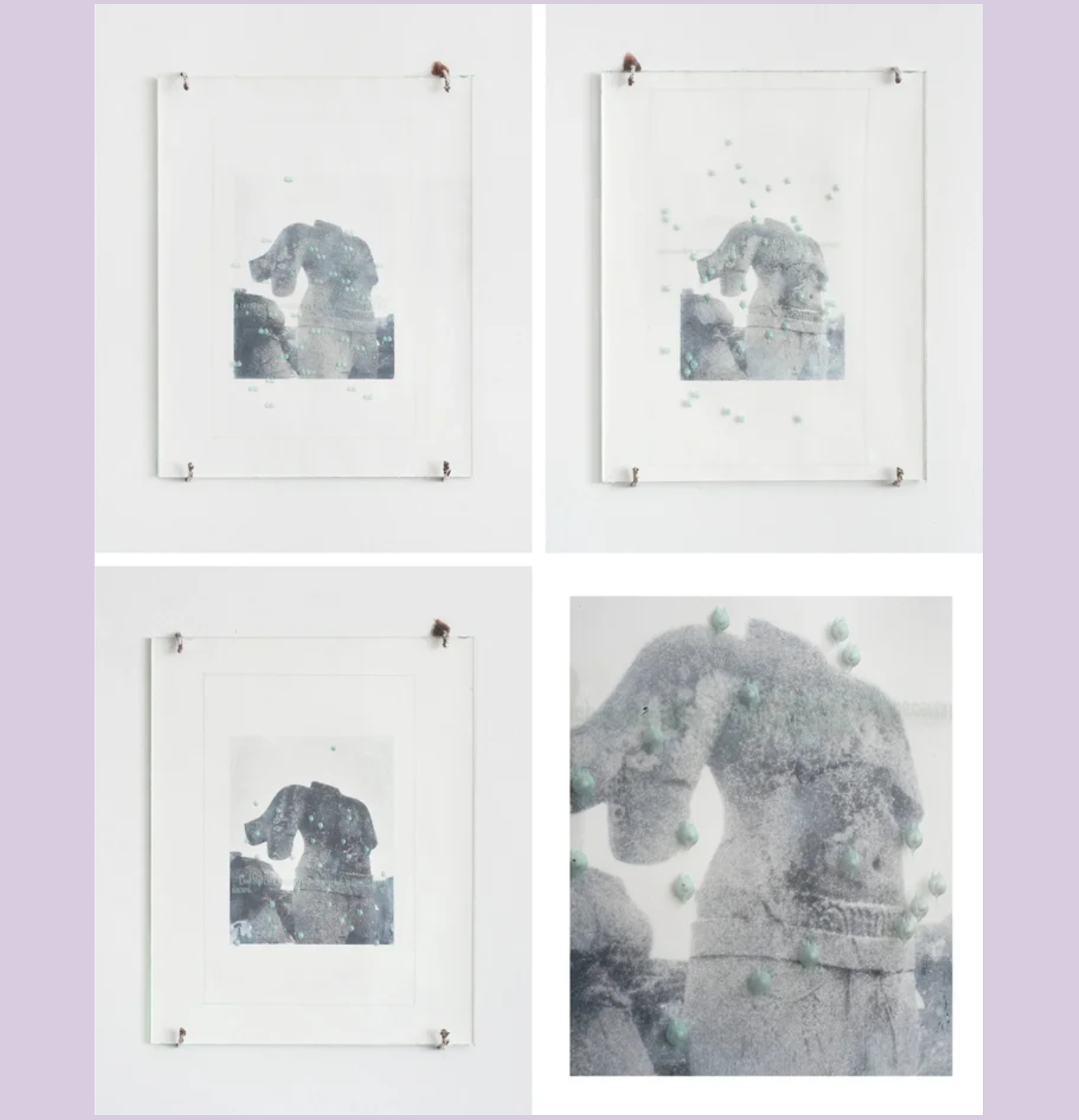

Clockwise from top left: Olhar é o necessário instrumento que, depois de usado, jogarei fora; Looking is the necessary instrument which, once used, I shall put aside; Looking is the necessary instrument that, once used, I shall discard; detail, all 2024, silver gelatin prints, silverpoint, inscribed glass, cast sterling silver L-hooks, soft silver solder, zinc oxide gesso, jeweler’s wax

Let’s bring this into connection with your use of photography. You had a recent teaching experience that offers an approachable way into your practice. Can you talk about that?

Aviva Silverman brought me on for a guest lecture for teens at the Dia Foundation this summer. We read Ghost Image by Hervé Guibert. At age eighteen, Guibert photographs his mother, images that are soon revealed to be lost because of an error in loading the film. With only the memory of the portrait session as his material, mourning the loss of the photographic image, Guibert transforms a photographic lacuna into an invitation to a new way of remembering: the text we are reading. This is the titular ghost image.

I had the teens think about a moment or period in their life of which no photograph exists. Pressing a piece of silver gelatin paper to our body, we walked in silence three times around the block while holding this memory in mind. It left this imprint. It gets to the heart of it: here’s a relationship that you can develop with the practice of image-making that is less about the image. Image-making is only one route to get there. If they create a story, then they eventually get this source material or seed to make these metaphorical, allegorical representations.

Which directly dovetails into one of the things I want to ask you about: the dance you play between sculpture and photography. You use the language of photography, even if the works do not read as traditionally photographic. Why is photography as a medium and as a language of interest to you and a challenge for you?

We engage with photography as social beings. I’m asking how we might work with or against the tools of image-making to find subjective ways of remembering, to retroactively photograph our past and photograph the unphotographable.

Is there a work that we can talk through this idea?

We can talk about vers(us). For about twelve years, I wore these watches that my parents gave me, one on each wrist. I’d started to think of these watches as a kind of ongoing work. The terminal point became clear as, last summer, both watches were inundated with seawater and I watched them rust and gradually stop.

Why I think about those as photo-based sculptures is because image is a time-based medium. Time is the lifeblood of photography. The watches were encased in beeswax that filled a copper frame measuring four-by-five inches, the size of a large format negative, a container for three nested images of time. Here are the parts of image-making that are metaphorically dissected.

In this work, the watch faces are not immediately seen, unless glimpsed in the reflection of the silver sphere between the frame and the wall. In another work, I RIDE SCENT, you hid a cigarette behind the glass frame. It is peeking out but I can imagine many people do not notice it. There is often an element of concealment in your work.

I use concealment in different capacities in each work, but if we’re discussing vers(us) and I RIDE SCENT in particular, the concealed objects are the starting point from which I develop the rest of the work. The work feels complete to me when a narrative flow emerges and the concealed object begins to feel like a superfluous appendage that is the site of productive ambiguity. That’s why photo-based sculpture is attractive to me; there are so many holes for ambiguity—productive ambiguity—throughout.

vers(us), 2025, Tag Heuer wristwatch worn by the artist from 2016–25, copper frame, silver solder, beeswax, silver sphere, flux residue

That idea of ambiguity is exciting to think about. You are looking for the tensions that exist within photography.

Photographic surfaces are less than stable. They are susceptible to deterioration, as are we. I’ve worked with negatives from my family archive that have been damaged by fungal growth on their surface. In my contemporary prints, these hyphae become clearly visible. I started to think about the instability of markers and how I was so drawn to the instability. So in that way, my sculptures that reference the language of image-making, I call them photo-based sculptures because they reference time as a medium. They reference the shape, dimensions, and the materials of time.

I am interested in how you took that experience of coming up against the limits of photography as a way to dig deeper into the medium: understanding its history, playing around with its physical components, employing its techniques in a more abstracted format.

The photograph alone never felt enough for me. Things began to make sense once I acknowledged my fixation with surfaces. I had to somehow work with the receptive surface as equal to the image, suturing its surface and materiality into coherence with the photograph.

When I was working only with images, it really interfered with my relationship with reality. Carrying a camera around, trying to find these things to photograph. I was never really a studio photographer. I was more interested in finding things in the world. It really confounded me for such a long time.

Another element of your decision to use the language of sculpture is the physical and bodily relation of looking at photos. Can you talk more about that?

Working in darkrooms has attuned me to the relationship between the body, time, and space. I’ve printed in the same darkroom for more than a decade now; I know my space intimately. In the darkroom, my movements take on a sharp, rhythmic quality coupled with the acts of conducting and carving light with my hands. I hold this embodied state in mind as I compose my sculptures. My sculptures don’t have a single, definite viewpoint. I think very specifically about how we typically show photo-based art versus sculpture. Photographs are meant to be looked at head-on. But as a photographer, you also enter into this choreographed movement with the space to find the optimal angle.

I RIDE SCENT, 2013–25, cast bronze frame, silverpoint drawing on silver gelatin prints, mirrored glass, FP100c Polaroid, beeswax, cigarette, neodymium magnets, 8.75 x 10.5 x 6 inches

You are identifying two different relationships—the photographer’s relation to the making of the work and the viewer’s relationship to experiencing the work. It relates back to Ghost Image, in which you have described that it’s about “making yourself visible in front of the camera.”

The reflective surfaces of my sculptures implicate you and the other people in the room. In another essay from Ghost Image, Guibert writes that the deflected gaze gains complicity and perversity. Viewed frontally, I RIDE SCENT reveals your reflection in an iridescent mirrored surface. It only reveals itself in full after you move around it and synthesize its multiple viewpoints.

Right, when I was in your studio, it took a few moments before I realized that I could see myself within the work.

To see yourself seeing, that’s exactly it. The act of photographing a subject is a duet, the photographer and subject moving in relation to and performing for each other. It is an act held together by an erotic charge.

At the same time that you are exploring the relationship of the viewer’s body to the work, you have also started a new ritual of taking a photograph of your nude body every day. It’s another example of you navigating your relationship with and to the camera.

This began with the simple pleasure of documenting my body as it alters chemically. I had no desire to show the images or even contextualize them as art. As it turns out, in the time between our conversations, I found a suitable container for these photographs. I’d been fabricating these welded steel forms. I titled them each Crossdresser, because I refer to them as travesties of minimal sculpture, travesti with an i, trans-vestire. Several of these images are rolled into scrolls and inserted into the welded forms. In my images, my camera is either a mask that obscures my face or I’m posing between a camera pointed toward a mirror, so that you, once again, see yourself seeing.

Part of this interview series is that I’m asking each artist to direct me to the next. So, who is an artist working today that you are intrigued by, and what is it about their practice you’re intrigued by?

While I trade in the evanescent, Maite Iribarren Vazquez’s work grounds me acutely in the material. She dissects mass-produced construction material, sometimes liberated from sites around the city, incising into them with surgical precision and lapidary attention to expose the absurdity within our social structures. I think about the frailty of our body in relation to the elements and the ever-resonant words of David Wojnarowicz: “in the shadow of the American dream, soon all this will be picturesque ruins.”

Published December 28, 2025