early shinada

Early Shinada is a poet-performer who seeks to create spaces open to interaction and possibility. In this conversation, we talk about their recent turn to writing and text, differences between a literary and performance venue, and the search for open-endedness. Born in Ohio, they are now based between Brooklyn and Hudson, New York.

I hope you enjoy our conversation. It has been edited from a spoken interview and condensed for clarity.

Artwork photos and portrait courtesy of the artist

Let’s start with your current collaboration with the gallery Salma Sarriedine, in which you are the poet-in-residence. Can you introduce this project?

Salma’s creative director, Aviva Silverman, and gallery director, Nadine Sarriedine, invited me to engage with the program through language. Many of the artists were new to me, so in some ways it was grounded in encounter: getting to know the artists, their work, and their hopes for the space. All of the shows have been multi-person pairings, so I approached each as an opportunity to feel the spaces between what each creator was positing and to serve as a kind of interstitial support.

Thus far, you have produced a unique text for each of the four exhibitions. The first was written on the gallery wall, the second was an invitation in a wax-sealed envelope, the third was also handed out but made from edible paper which guests were invited to eat, and the fourth was inscribed onto the mirror in the bathroom.

The first was a large group show. There were so many people and kinds of work, so many themes. The unifying thread invoked for me was a sense that, in this moment when we're seeing so many world systems be destroyed, the artists were answering varied calls to create new ones. So I wrote a call to bravery. I put the text on the wall to both set the space and leave space for the other works. I made a paint by grinding bricks down into a powder reconstituted with honey and gum arabic. I’ve been returning to this idea from sociologist Zygmunt Bauman in his book Liquid Life. He is trying to make sense of how we live under conditions of constant precarity. He uses “liquid” as a shorthand to name that immersive instability and identify the adaptive skills needed to inhabit it. The show felt evocative of this double bind: a longing for orientation or even origin in the face of immensely pressurized change. I re-staged a shared predicament by disintegrating this structural material of the brick, forcing it into a pulverized fluidity, and then pressing that into this sweet, nutritive, and communicative state with honey.

By the nature of it being text on a wall at the exhibition entrance, I imagine that it also disguised itself in the form of a familiar gallery text that viewers would look to for understanding or framing the show.

Functionally, it did.

Splitter, 2025, pulverized bricks, honey, gum arabic

How did that work inform your approach for the subsequent texts?

That first collaboration opened this question of, what does it mean to physicalize language? How does text become bodied, and why?

For the second show, I made an invitation. The show was so visceral. Miguel Colón’s paintings presented us with naked figures pressed into confining institutional spaces of uneven surveillance. Savannah Knoop’s sculptures provoked a discomfort around one’s relative passivity while sensuously inviting interaction. The room felt like an arena. You couldn’t be there without becoming conscious of your own positioning in a live field of contact and power. I made this invitation, which like the most mundane invitation, operates as a kind of threshold. You are handed the invitation, you may choose to crack the wax seal and open it, and then you may choose to join. I wanted that series of choices to prime people to enter the space already switched on. The first line was a dare: “let’s play chicken.”

The third, the edible poem, was also situated in a process. Each visitor was presented with an envelope and asked to enter into a compact: if you accept this, you must also eat it. The text was a visual poem, seating “WHAT CAN BE” and “WHAT WILL BE” in an axis hinged on “I WILL.” The show was themed around global scale struggles for justice, so I wanted to instigate a small ceremony of commitment in that context. It played with language as elemental and related to our infancy and the ways we’re brought into the world and fed. We ingest it from the people around us and then give it to others through our mouths or hands.

This opportunity feels like a laboratory. Several factors remain the same each time: the prompt, the general space, the use of text. And then other factors you can change: namely the text’s form and content. A preoccupation with text and language extends to much of your practice. When we first spoke, you introduced me to an early work in your practice—a book that disintegrated over time. Can we talk more about that?

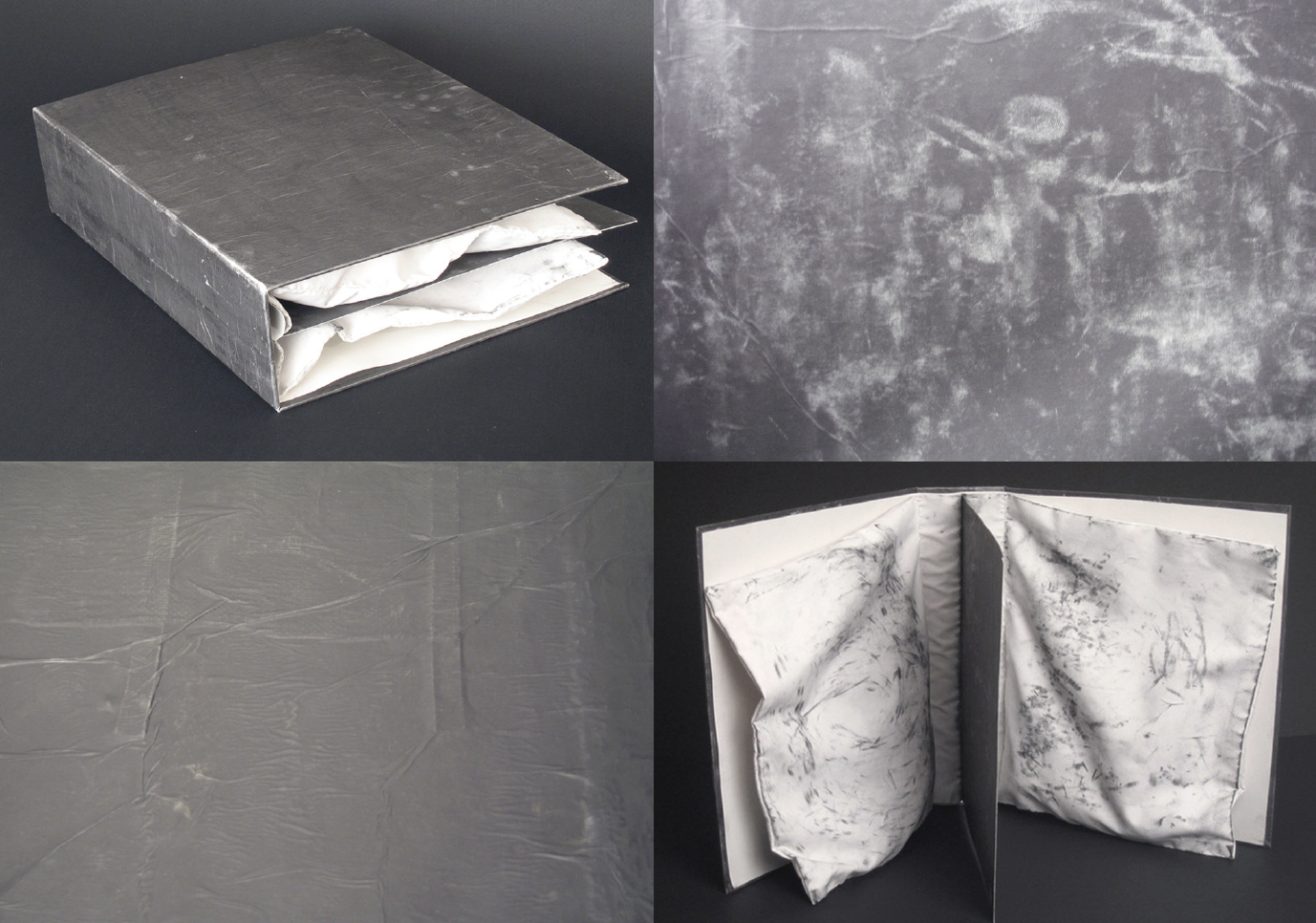

That piece I made maybe fifteen years ago. It was essentially a palimpsest of itself, a kind of self-recording object. There were “pages,” I’ll call them tactile fields hidden from sight in cloth bindings that alternated with transfer-paper pages. As people met it, it would record each contact but also its touching of itself as the carbon transferred between the parts to create these visual traces. And then its trail was extended by both additive and subtractive marks that also polluted its surroundings as it rubbed against the plinth or people’s fingerprints spread in the space.

Over time, the more interactions, the more flipping, it becomes less usable, less legible.

It was constantly being disordered. The unseen elements of the fabric pages were unstable and would change. As people discerned the pages via touch or even contrived to create specific marks with the carbon, the experience that removed the “text” was being undone as it was being recorded.

It became a collective record while also refusing to be a reliable record since it inevitably cannot last.

The book is a thing we receive in its predetermined state. But when we read, we do change it, right? So it's live. It was an invocation of that. Making a thing that resisted being final, a thing that was live with the people that met it and had a life beyond me and my making of it.

I like trying to think of how to make a book alive.

I was in school at the time and it was a prototype for me in asking the question of, how can we become active points in the transmission and reception of knowledge? How do we stay awake to the experiential flow by which we come to know what we know? When we lose track of that, the rich bodily aspects of discovery, reception, rejection, and expression, we end up in these dangerous tendencies, like fantasies of omniscience or false universalism. Staying with the sensual as a vital territory of knowledge puts us in touch with our limits in a generative way that also paradoxically grants us access to our own authority.

In that way, it’s really resonant with the way I engage with writing and performance today—as this surrender to what will become. Surrender to the digestion or transformation in reception, whether it’s literal digestion in the case of the edible poem or the way it is morphed in contact with the listener. I am really interested in the threshold of opting in and the choice of engagement. A prerequisite to that choice is taking on the risk of being changed, out of control, or misunderstood.

Spread, She is catching, 2010, modal fabric, binder board, carbon transfer paper, linen tape, cotton thread, 29 x 18 x 3.5 inches

I would love to take some of those ideas—surrendering, opting in—and consider them in the context of your performances. What do you hope for when you stage one of your performances?

The performances of mine that I think are most interesting invite people to relate to each other, not just script them to be the audience to receive something. It is always a collectively generated convening. Ideally, it's about creating the conditions for something to happen that wouldn’t have happened otherwise.

During a performance at the Park Avenue Armory, I looked up to see many people crying. It’s wild to do something as simple as speak and realize it has moved someone in that way. Often people come talk to me afterwards, to share personal histories or constellations of meanings that got pulled for them. Then there’s this dialogue, people breaking into these depths even as they are meeting for the first time. It creates movement. I’ve met friends this way. I’ve learned and been challenged to argue. That’s the thing for me, in these live moments we invite one another to move into contact and change and sometimes even build new social networks.

This goes back to a term that you used previously in this conversation—“the encounter”—which I understand to mean an interest in the unplanned potential between performer and audience, between the audience members, or between multiple ideas or texts being offered.

Nothing I make is completed, except in its reception and what happens in that encounter. Every expression is fed by those I’ve received. So it’s always open on all these different sides. When I’m writing, I bring together disparate histories and traditions of thought. I’m often working to open history up from or to life, for example recounting my grandmother’s choice to evacuate at the start of the bombing or tracing the pilot’s testimony of what it felt like to drop the bomb. I’m fascinated by the ways grand-scale historical narratives impress themselves into people’s lives and how we inhabit the live processes of history.

Early Shinada at KAJE World, 2022. Photo by Luke Herrigel

Lately you have been participating in “readings” within literary settings, which is different from performing in the art or music settings you are more familiar with. How has that experience been for you?

It was COVID when I started writing, and I wasn’t thinking about performance because that space wasn’t there. Later I learned that the literary reading is a primary form of engagement for how a writer can bring life to what can be a very solitary process.

How did you, or do you, experience those spaces?

At first it was very alien: to act like we are in school, the ways we’ve been trained to demonstrate attention, like holding still and quiet. It was an adjustment after performing in music spaces where people are very self-authorized to move or react. But I’m learning as I do it more and respecting what it can be for people to have that space to be inward and contemplative. And then there’s just being in the room with people. In NYC, that scene is a scene, it’s like a community. Something gets created as people come together over and over again.

Having been to both literary readings and art performances, I am aware of the different ways that I comport myself in each. In readings, I am mainly focused on listening. In performances, I am more focused on watching. Let’s talk for a moment about what you are reading in those spaces.

One of my guiding fixations is the question: how do we know what we know? I study and write about the past to surface insights that are actionable in the present. A lot of my writing lately has been pressing the tension between ways of knowing. When I write about my own experience or family history, one reason I do so is to model the way that we can honor our lived understanding as a source of knowledge.

There’s history, this whole intellectual discipline with gatekept roles and demands for what can be said to be the thing that happened. But it’s a troubled process. As Churchill, of all people, said, “history is written by the victors.” I see our experiences, lived and felt, as core to understanding what’s true, especially when we need to insist on truths external to that story of the victors. That’s not to champion the individual over all else. On the contrary, when we pay attention to the way we assemble our sense of the world and what’s possible, we can’t help but see that we build our knowledge through one another, via visceral transmissions of fear, confidence, belonging. This understanding is also fallible but can puncture the often flat and distorted official narrative to restore the complexity of our collective memory.

Through your writing, and then performing, you are working to both assemble and disassemble knowledge.

Exactly.

Do you have a sense of what’s next for your practice?

Coming from a DIY background, I’m thinking about creating spaces that can foment experimentation. There’s this crisis with arts and educational institutions folding under political pressure to basically collapse freedom of belief and action, and an accompanying crisis of aspiration amongst artists and thinkers. I sense a growing wish for more open arenas. This summer I participated in a mobile free-school project, supporting dozens of people to teach a wide range of hands-on skills, analytic frameworks, and histories. I feel excited by the possibilities we can continue to create with one another.

At the same time I’m working on a book, so I’m learning how to engage with that new form.

Part of this interview series is that I’m asking each artist to direct me to the next. So, who is an artist working today that you are intrigued by, and what is it about their practice you’re intrigued by?

Zhi Wei Hiu is an interdisciplinary artist hybridizing various analogue creative and chemical processes, like darkroom photography and metalsmithing, to create these exquisite sculptural forms that, to quote Joseph Beuys, “make the secrets productive.” As you peer through layered reflections, iridescences, and burns, the pieces feel to be in a still-active process of material formation. I love that her work pulls me into a slower time and attention.

Published September 7, 2025